Title

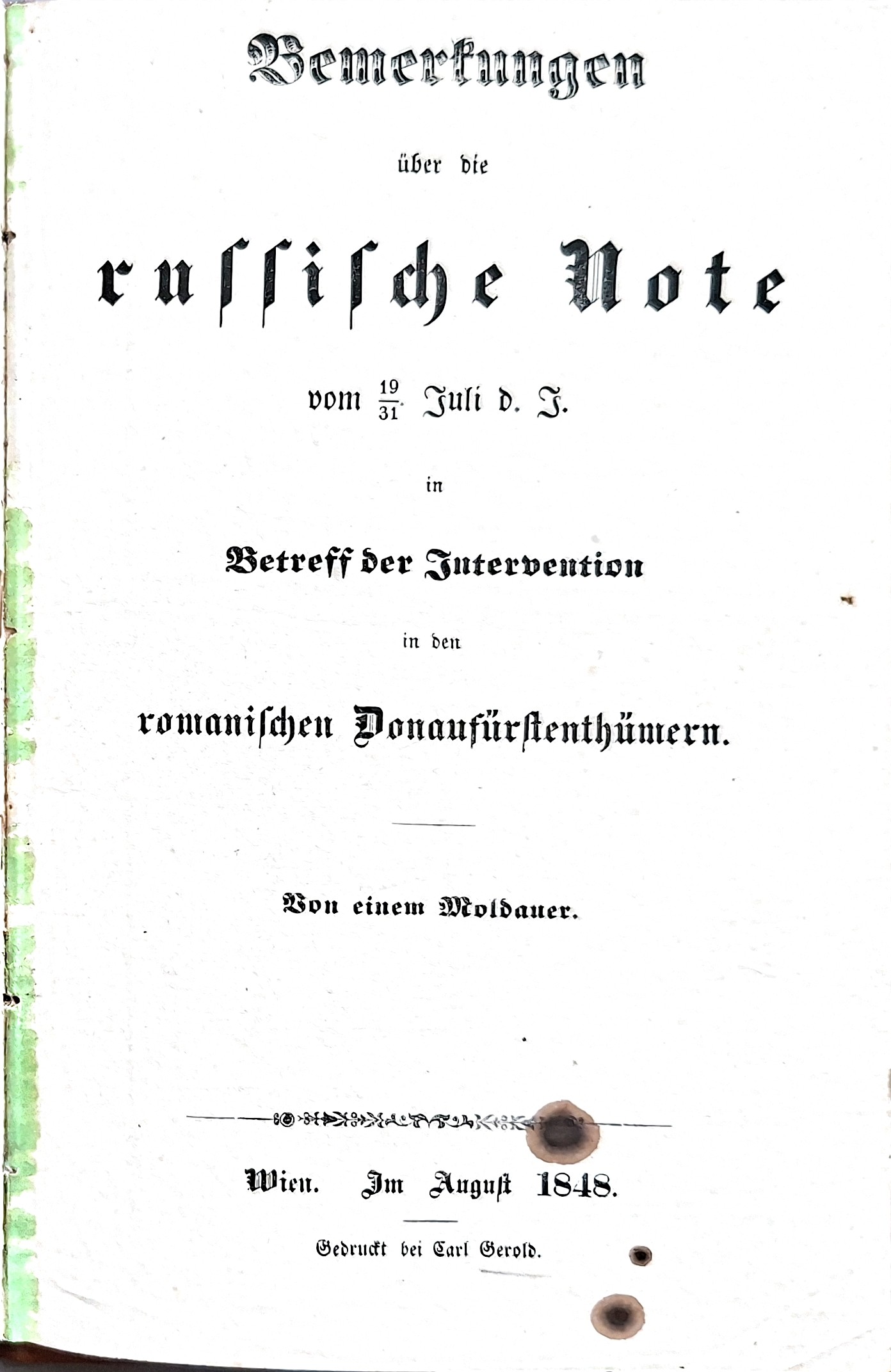

Bemerkungen über die russische Note vom 19/31. Juli d. J. in Betreff der Intervention in den romanischen Donaufürstenthümern. Von einem Moldauer.

Remarks on the Russian note of 19/31 July 1848 regarding intervention in the Romanian Danubian Principalities.By a Moldavian

Editor

Vienna, Gerold, August 1848

Description

This document is a detailed political and legal critique of the Russian note dated 19/31 July 1848 concerning the intervention in the Romanian Danubian Principalities, specifically Moldavia and Wallachia. Written by a Moldavian author in August 1848, it addresses the legitimacy, motivations, and consequences of Russian actions in the region, while also discussing the historical sovereignty and rights of the principalities under Ottoman suzerainty and Russian protection.

Overview of the Russian Note on Intervention

The Russian circular note outlines the justification for military intervention in the Danubian Principalities due to revolutionary upheaval threatening the established order. It claims that the principalities are not sovereign states but provinces under Ottoman suzerainty, governed by princes whose election requires confirmation by the Ottoman Porte and Russia. The note asserts that the revolutionary movements aimed to overthrow this order and establish an independent Daco-Roman kingdom, which Russia perceives as a threat to regional stability and its own security interests, especially in Bessarabia. Russia emphasizes that its intervention is lawful, based on treaties with the Ottoman Empire and is conducted jointly with Ottoman forces, with the promise of withdrawal once order is restored. The note distinguishes this intervention from Russia’s policy toward independent European states, maintaining neutrality in their internal affairs.

Critique of the Russian Justifications

The Moldavian author challenges the Russian portrayal of the events and the principalities’ political status. Contrary to the Russian claim that only a rebellious minority sought reforms, the author argues that the broader population supported the new institutions and reforms aimed at eliminating corruption. The alleged plans for a Daco-Roman empire are described as exaggerated political fantasies rather than genuine nationalist movements. The assassination attempt on the Wallachian Hospodar is attributed to a few individuals, not the nation as a whole.

Legally, the author disputes Russia’s denial of the principalities’ sovereignty. The Danubian Principalities had historically been sovereign states with their own elected voivodes, maintaining internal self-government and external representation despite Ottoman suzerainty. The capitulations with the Ottoman Porte explicitly reserved internal sovereignty and rights such as legislation, administration, war, and peace. The author emphasizes that treaties between Russia and Turkey cannot diminish the principalities’ rights gained through earlier capitulations. Russia’s claim that the principalities have no political existence beyond what its treaties grant is therefore contested as unjust and contrary to international law.

The Nature of Russian Protection and Its Consequences

The document questions the nature and benefit of Russian protection over the principalities. It portrays Russian influence as corrupting and destructive, exemplified by the figure of Michael Sturdza, a hospodar described as a tyrant who undermined the country’s moral and political integrity. The author argues that Russia’s protection has become a form of control that undermines the principalities’ autonomy and serves Russian interests rather than those of the local population. The proclamation of popular sovereignty by the principalities is seen as strengthening the Ottoman Porte’s suzerainty rather than diminishing it, while Russian protection is characterized as increasingly oppressive.

The author further critiques the Russian-imposed Organic Regulations, which replaced aristocratic institutions with assemblies dominated by boyars loyal to the hospodars, effectively consolidating power in a corrupt elite rather than promoting true democratic or socialist reforms. This electoral manipulation is presented to suppress opposition and maintain the status quo favorable to Russian interests.

Political and Strategic Analysis

Politically, the author reflects on Russia’s broader ambitions in the Orient, suggesting that Russia seeks to reshape the region according to its own designs, contrasting with other European powers that prefer to maintain the status quo. The document warns that Russia’s interventionist policy risks alienating the principalities and losing their sympathies, which had been won previously through more benevolent governance. The author advocates for Russia to adopt a policy of goodwill, allowing the principalities to reform freely and regain their dignity, which would better serve Russia’s long-term interests and European peace.

Historical and Legal Context of the Principalities’ Sovereignty

The appendix provides a historical overview of the Danubian Principalities’ sovereignty. It traces their origins as sovereign states ruled by self-elected voivodes, maintaining independence despite alliances with Hungary and Poland. The submission to Ottoman suzerainty occurred voluntarily, with explicit reservations of internal sovereignty, including rights to self-government, legislation, war, peace, and diplomatic representation. The document cites legal scholars affirming the principalities’ sovereignty or semi-sovereignty, emphasizing that Ottoman suzerainty did not revoke their essential sovereign rights. The author argues that Russia’s treaties with the Porte cannot override these foundational agreements and that Russia’s intervention infringes on the principalities’ rights and the integrity of the Ottoman Empire.

Conclusion

The document concludes by appealing to the great European powers to recognize and enforce the true rights of the Danubian Principalities. It calls for peace and freedom to coexist and warns against further provocation or suppression of legitimate aspirations for reform and sovereignty. The author expresses hope that the powers will prevent ruin and uphold the law, emphasizing that freedom and peace are inseparable.

This comprehensive critique highlights the complexities of sovereignty, international law, and power politics in mid-19th century Eastern Europe, providing a nuanced perspective on the Russian intervention in Moldavia and Wallachia.

Date

1848 ( dated )

Dimension

Page count: 26

Author

Anonymous According to Mr. Victor Taki, author of “Russia on the Danube”, this article could be written by Mihai Kogălniceanu. The general character of the argument promoted in this publication resembles what Kogălniceanu wrote at the end of “The Wishes of the National Party in Moldova” from August 1848 and in “The Rebuttal of the Russian Dispatch of 19 July a. c.”, article from the “Gazeta de Transilvania”, written by a Moldavian (M. Kogalniceanu), included into “Year 1848 in the Romanian Principalities”, ed. Ioan C. Bătianu, vol. 4 (Bucharest: Carl Göbl, 1903), 335 - 341. Also, the author of “Bemerkungen” mentions Martens and other German legal authors, and this is in agreement with the fact that Kogălniceanu studied in Berlin under Friedrich von Savigny.

Reference

Translation

Remarks on the Russian note of 19/31 July 1848 regarding intervention in the Romanian Danubian Principalities.

By a Moldavian.

Vienna. August 1848.

Printed by Carl Gerold

[Page 3]

We read, strange as it may sound, with a certain pleasure the dispatch that the Russian Cabinet sent to its representatives regarding the occupation of Moldavia. However, this pleasant feeling we experienced should in no way be attributed to its content, but only to the fact that the absolute power, deviating from the principles it had previously followed, intended that dispatch not only for communication to the courts concerned, but also for public view. From this it seems clear that Russia also recognizes public opinion as a power to which it owes an account for its actions. And while we welcome it in the new field it has entered because of its progress, we undertake, without partisanship, to criticize that act. We therefore allow this Russian note in its entirety to precede our remarks.

The Russian note on the intervention in the Danubian principalities

This circular note, dated July 31, addressed to the Russian ambassadors abroad, which is of particular interest because of its numerous hints about Russian policy in general, reads in full as follows:

“The situation of the Danubian Principalities, whose peace had been threatened for several months by a turbulent minority, has suddenly taken such a serious turn that the emperor was no longer permitted to ignore them. You know the events that have recently taken place in Wallachia, the assassination attempts against the person of the Hospodar, his abdication and flight, the recognition of a [Page 4] provisional government and the principles enunciated by this authority, which was brought into being without further ado by the insurrection, the sovereign power responsible to the Ottoman Porte, in obedience to, and in open contradiction with, the Protectorate of Russia. No sooner had the revolutionaries’ plan succeeded on this side than they immediately set about extending it to Moldavia. A few Wallachian and foreign emissaries had already spread there. The Moldavian boyars who had fled to Bukovina were gathering forces to march against Jassy, and the party members, together with their allies in Transylvania and even in Bessarabia, were preparing an uprising whose result, as in Wallachia, was to be the murder or expulsion of the Hospodar, the overthrow of the existing order, and the unification of the two principalities into one state without any connection with Russia or the Ottoman Porte. Faced with such circumstances, we need not hesitate. The Porte, for its part, recognized that this was a matter of its own gristle (qu’il y allait de sa propre existence). Accordingly, the two Powers, to whom alone, according to existing treaties, the right to regulate the affairs of the two provinces belongs, have agreed to restore the order they had established there, and to this end, their combined troops (leurs troupes réunies) have entered them to act jointly. It was not without strong regret or mature consideration that the emperor decided to take this important measure. In the present situation in Europe and the prevailing mood, His Majesty would have far preferred not to have been forced to abandon his immobile attitude. In and of itself, the fact that Russian troops have crossed the Reich’s borders must cause considerable attention. It opens-and we do not conceal this from ourselves-all malicious [Page 5] a clear field for interpretations. We have steadfastly denied any plan of intervention, any interference in the affairs of others, all ideas of aggression. Our agents abroad have recently been instructed to renew these assurances in Germany. Now, under the current circumstances, attempts will undoubtedly be made to counter these declarations to bring us into conflict with ourselves, if possible. In the eyes of those who mean well, this contradiction does not exist. We have, however, declared that we will not interfere in the various transformations to which our neighboring states might be inclined to subject to their internal constitutions. But it is perfectly clear that such a promise could only apply to those European states that negotiate with us as power to power, to the independent states whose social organization bears no relation to the political treaties that have determined their territorial extent. Regarding these, we neither claim to exercise any kind of influence. The situation is different with the Danubian Principalities, which are not recognized as states, but are nothing more and nothing less than provinces forming an integral part of an empire, subject to tribute to their sovereign, temporarily governed by princes whose election requires confirmation, and which, as far as Russia is concerned, have no political influence at all, except insofar as the treaties concluded between the Ottoman Porte and us are concerned-treaties which, in turn, have nothing in common with the totality of transactions on which the public law of Europe rests. Only to these treaties, and especially to those of Bucharest, Akkerman and Adrianople, do Moldavia and Wallachia owe those privileges which have been added to or substituted for those which they originally possessed by their old capitulations with the Porte [Page 6] - the method of electing their hosts, the exemption from burdensome taxes, which was replaced by a more moderate annual tribute, their free practice of religion, the freedom of their industrial activity, their navigation, and their trade, even the extension of their borders through the annexation of the associated Danube islands and the Turkish cities and territories lying on the left bank of the Danube to Wallachia. Finally, through these very treaties, the enjoyment of the form of administration by which they are governed has been guaranteed to both provinces, and this form of administration itself is determined by an organic statute introduced with the consent of the Porte, so that, on the one hand, the Moldavian-Wallachians are assured of the privileges granted to them, and, on the other, they are preserved in the relationship of vassalage that binds them to the Ottoman Empire. It follows from this quite exceptional, quite special position, based entirely on the agreements concluded between the Ottoman Porte and us, that Moldavia and Wallachia have positive obligations to fulfil both the sovereign and the protector power, obligations which they cannot evade without the prior consent of both. It is possible that their administrative regime is susceptible to improvement, that it must even be modified in more than one respect; but this cannot be done without the consent of both courts, and it cannot be done through revolt. Now, revolt is the means employed by the leaders of the victorious party, not merely to modify this regime, but to overthrow it fundamentally. Forgetting that most of the advantages assured to their fatherland are due solely to the benevolent protection of Russia, they reject this protection to appeal to the protection of other powers. Their duties towards Porte are no less seriously misunderstood. For even if they still pretend that they do not want to destroy their vassal relations with it, they nevertheless destroy them in the fact [Page 7] by abolishing, at their own discretion, all rules and conditions that form the basis of these relationships. The principle of popular sovereignty, invoked as the basis of their pretensions, is already sufficient to represent the most decisive negation of the Sultan’s sovereign rights. Moreover, their further plan is openly disclosed. It follows from their program, and their proclamations make no secret from it. It consists in establishing their old nationality on a historical basis that never existed, i.e., in ceasing to be provinces and, under the name of a Daco-Roman kingdom, in creating a new, separate and independent state, to whose formation they will invite their brothers in Moldavia, Bukovina, Transylvania, and Bessarabia. The realization of such a plan, even if it were admitted that it was to come to fruition, would entail serious consequences. If the Moldavian-Wallachians succeed in separating themselves from Turkey under the name of a supposed nationality whose origins are lost in the darkness of time, we will soon see, in accordance with the same principle and under the influence of the same desire, Bulgaria, Rumelia, and all the provinces separated by language that comprise the Ottoman Empire, also claim emancipation for the purpose of establishing separate states. This would result in either complete fragmentation or at least a series of inextricable complications throughout the entire East. If this were only a matter of the instigators of the uprising, and if they truly represented the opinion of the Moldavian-Wallachian people, which we do not believe, we could, despite all the reprehensible aspects of their behavior toward Russia, to which their fatherland owes the advantages of its present situation, remain indifferent to the oblivion with which they treat our benevolences, and leave them to the consequences of their foolish and guilty enterprise. But this small number of madmen, whose governmental ideas are merely plagiarism, what [Page 8] they have borrowed from socialist and democratic propaganda, foreign to their own homeland, cannot, in our eyes, apply to the true Wallachian people. And even if that were not the case, the more we have done for the principalities, the more we have influenced them at the Ottoman Porte, the more it is a matter of honor for us to prevent them from abusing these advantages to the detriment of an empire whose integrity, in our eyes, is more than ever an essential condition for maintaining general peace in the current upheaval in Europe. Our own security, moreover, is also involved. It is threatened in Bessarabia by the intrigues being hatched there, by the presence of a hotbed of continual insurrection that would thus arise at our doorstep. It would be just as unsuitable for us as for the Porte itself to allow a new state to rise in place of two principalities, which, exposed to anarchy and too weak to maintain itself by its own strength, would sooner or later inevitably fall under the domination of other powers, thus endangering all our international relations. Therefore, for us, this is simultaneously a question of law, a question of honor, a question of political interest, among all things to which Russia may neither consent nor transgress.

These, Sir, are our motives for intervention. They are simple, they are legitimate. But since people have unfortunately become accustomed to treating Russian politics with skepticism, to seeking in it what is not there, and since, moreover, the interest of the anti-social party, which only wants a general conflagration, is to disturb and embitter public opinion, we have no doubt that the movement we have undertaken beyond our borders will, as usual, give rise to the most false suspicions. It will be said, and it has already been said, that this [Page 9] movement is only a first step in our policy of consolidation; that we only waited for a pretext to advance our armed forces; that we entered the principalities, fully determined not to leave them again; and that, in accordance with the traditional plans for aggrandizement which Russia harbors about the Turkish Empire, we are, to carry them out, exploiting the difficulties into which the social disturbances of the present have plunged Western Europe. We have only one very simple fact to counter all these conjectures: namely, that we entered Moldavia because of an agreement with the Ottoman Porte, and that our troops there, foreseeing that it would be necessary, will act only in conjunction with theirs. The past, moreover, guarantees the present. More than once in former times we occupied the principalities in whole or in part, and, true to our previous word, we have always vacated them as soon as the conditions we had attached to our withdrawal were fulfilled. It will be the same again now, and as soon as legal order is restored in Wallachia, or the Porte believes it has obtained sufficient assurance for the continued peace of both provinces, our troops will be withdrawn from them, to immediately resume the strictly defensive position they held on the border. The conclusion you will have to draw from the following considerations is that, since the relations between the Danubian Principalities and us offer no analogy with those between Russia and the other European powers, our present intervention has nothing in common, neither in principle nor in fact, with those which one would wrongly suspect us of attempting elsewhere in Europe. Our rights in the East are based on treaties which do not exist in the West. Please endeavor to [Page 10] to make this important difference particularly prominent. It is visible to anyone who wants to see it; the intervention therefore detracts nothing from the value of our previous declarations. With regard to independent states, our principle of strict neutrality remains unchanged; and whatever changes one or another of them may make to their social and political laws, we will, as long as they do not attack our security or our rights, continue, as we have done until now, to watch, rifle in arm, the spectacle of their internal upheavals.

Nesselrode.”

A great affliction of absolute states, which the monarchs themselves may feel most deeply without being able to remedy, is certainly the circumstance that the Russian people express so pithily with the proverb: God is high, and the emperor is far, which proverb refers to the injustices that take place without the knowledge of the emperor. The first thing we must do, therefore, is to eliminate everything that found place in that dispatch because of the emperor’s removal due to false reports.

Accordingly, we affirm that it was by no means only a rebellious minority of the nation that demanded reforms to eliminate corruption; for it cannot be denied that Wallachia is satisfied with the new institutions it has established, if only it were allowed to consolidate its achievements in peace. Moreover, why speak of majority and minority if one does not want to recognize their principle?

Furthermore, far-reaching plans and actions are attributed to the Moldo-Wallachian reformers, which one cannot fairly burden them with and which cannot be proven. That many Wallachian or Moldavian may have indulged in the harmless dream of a Daco-Roman empire is certainly possible; but it is not and cannot have been more than a poetic political license. A small people, systematically abused by a corrupt government, which is not independent, which has forgotten how to handle weapons, how can it indulge in the delusion of not only maintaining its independence in the midst of three powers without their consent [Page 11] to conquer, but by force of arms, independence from Turkey, Bessarabia from Russia, and Bukovina from Austria? One can certainly inflame many noble spirits through agitators, through deceptions, through artifices, and the like, and excite the hearts of young men with dreams that bring accusations like those contained in

the dispatch, but an entire population cannot possibly allow itself to be misled into trying to realize pious wishes by force. As for the recruitment and intrigues in Bukovina and Transylvania, and even in Bessarabia, as is alleged, the Austrian government probably knows best that perhaps here and there such things were spoken of, but certainly no one was recruited. Now the question arises whether a Daco-Roman dream and the talk of recruitment, at a time when so much is dreaming and talking, justify Russia in occupying Moldavia.

The Hospodar of Wallachia was shot at! Yes! But was the nation involved in this? No; for its provisional government, when he voluntarily wanted to leave the country, gave him passports to go to Transylvania. Consequently, it did not seek his life. But the fact that a few shallow minds were found who, seized by a criminal delusion, wanted to become prince murderers can in no case be the fault of the nation. Who, for example, could accuse the Prussians of intended regicide because a depraved man, whose name has slipped from us into well-deserved oblivion, attempted to take the king’s life?

These conditions, which form the basis of the dispatch as facts, were brought into clear light right at the beginning, and now we turn to the question from the point of view of law.

After the dispatch explains the system of non-intervention in the affairs of the Western states, it denies the Danubian Principalities any political existence, except that granted to them by Russia’s treaties. It thus deprives the Danubian Principalities of all rights which they reserved for themselves in their capitulations with Turkey. But Turkey’s rights to Moldavia and Wallachia are based precisely on those [Page 12] Capitulations, which grant it supremacy over sovereignty and an annual tribute, subject to the reservation of all other sovereign rights. They are consequently the foundations of the legal relations between Turkey and the Danubian Principalities, and these capitulations are also the basis of the treaties concluded between Russia and Turkey. Now the question arises, why should the principalities, as the dispatch claims, have no other political existence for Russia than that which its treaties with Turkey give them? Moldavia and Wallachia have never fought against Russia; on the contrary, they were, if not in form, then in fact, Russia’s allies, for they have always faithfully supported her in her wars with property and blood; consequently, they could not lose any of their rights to Russia through conquest. While it is recognized as an unlaudable act to do something in to take peace from another state without a prior declaration of war, without stating the reasons why; all the more so, it cannot be permissible to whimsically infringe the rights of a country through peace agreements, which has contributed to the achievements of this very peace to the best of its ability. But Russia is doing this; for if it wants to condition the existence of the Danubian Principalities merely according to its treaties with Turkey and leave the capitulations with Turkey to expire, it will deprive the Danubian Principalities of all the rights they reserved to themselves with the capitulations, and it means clearly telling the Moldavian Wallachians: You have stood by me faithfully in order to lose rights, not in order to acquire them. But that cannot be pious, noble, or just, and we hope not the emperor’s intention. The Danubian Principalities could, as already mentioned, have contributed to the wars. Russia may gain rights with Turkey, but by no means lose any, and if treaties with Turkey, which, as already noted, have capitulation as their basis, nevertheless stipulate provisions contrary to those capitulations, then Turkey thereby has the indisputable principle: Nemo plus juris in alterum transferre potest, quam ipse habet [Page 13] exceeded, and the Danubian Principalities are not obliged to recognize those stipulations insofar as they impair their rights. They remain entitled to object to them in full.

The dispatch claims that the Wallachians have dissolved the alliance that existed between them and Turkey, if not formally, then de facto Far from wanting to dissolve this alliance, the Wallachians are firmly convinced that under the current circumstances, when Austria is so preoccupied with its internal affairs, when it is so important to establish peace and quiet, and therefore to avoid anything that could raise new questions and consequently new complications, it is advisable, we say, to strengthen this alliance more firmly, to loosen it completely, and if time and circumstances should require a different arrangement, a change in the East, only then, with the agreement of the Great Powers and especially with the approval of the Imperial Porte, to do their utmost to bring about a new arrangement by peaceful means. By virtue of their capitulations, the Wallachians have changed their internal state institutions and shaken Russia’s protection, but this in no way constitutes an infringement on the right of sovereignty. On the contrary, people have returned to the conviction they had lost that they have much, very much, to expect from Porte. No! One must not accuse the Wallachians of wanting to impair the rights of Turkey, and by undermining Russian protection, the Porte’s prerogative can only gain, not lose!

What should protection be, and what are its characteristics?

It must necessarily emanate from a state that protects a weaker party from the encroachments of a stronger party.

It must have a beneficial effect on the weaker party, otherwise it does not correspond to its basic conditions and destroys what it promises to preserve.

It eliminates the need to be subdued and, consequently, cannot be an exclusive privilege

As far as the Protection Russian has fulfilled its conditions, it would be too much to sweep and too far, now we see and need our reference to bao us [Page 14] which has already been written about in travelogues and newspapers. For reasons of space, we will therefore limit ourselves to providing evidence that since the Russo-Turkish peace treaties, with which Russia’s influence took root in the Danubian principalities, these countries, far from progressing towards prosperity, have, on the contrary, only been exposed to their ruin.

Moldavia and Wallachia, despite the corruption that has taken root there and threatens to corrupt the moral life of the people with its poisonous fruits, are nevertheless countries where customs and habits are permeated by the purest morality. But one should not look for this morality in the higher classes, for there it has long since given way to poison, but in the patriarchal life of the people, and consider that the higher strata of society in the principalities were once animated by the same spirit that still burns within the people for in earlier times, a nobleman on the lower Danube was nothing but the patriarch of a great family. “Abandon your customs, reject your rusty habits and institutions, relinquish your privileges, and trust me; for I want to lead you on a new path of civilization,” Russia said to us. The naive Moldavian-Wallachians trusted their co-religionists, and they surrendered their simple, pure customs to self-interest, honor, and a thirst for order; their customs and institutions inherited from the Romans to a plagiarism of Russian institutions; and finally, their privileges to an all-poisoning bureaucracy. What did they get in return? A Michael Sturdza, who morally ruins everything that comes near him, not excluding his own sons. An emissary of sin, a hellish serpent wrapped in a princely mantle, a landowner who squeezes the poorest pennies, a peddler of the fatherland who, to be able to drain his land unhindered, did not have the courage to ask the powers that planted him for the good of his fatherland when they made demands that infringed on the country’s rights; a cowardly tyrant who trembles for his own sinful life by wanting to shed innocent human blood; a prince who undermined the sovereignty because he turned all hearts away from it, who dishonors his dignity and the hand that supports him because he stains it with his deeds; a monster who carries on his conscience the [Page 15] ruined future of a country, and, under the crushing burden, seeks courage for new atrocities in churches and prayers, not realizing that one cannot ingratiate oneself with God as one does with earthly mortals through lies and deceit, not considering that one can only receive peace of mind from God through sincere repentance, which he completely lacks. Russia knows this man very well; it does not deny him these shameful qualities; it has even obliged him to return his valuables. We therefore expect no opposition from the East. But nevertheless, when the country, in justifiable resentment, perhaps wanted to revolt against its moral murderer, Russian soldiers are sent to his aid to protect the princely dignity in Moldavia, not considering that the imperial dignity might suffer by allowing its banners to protect a hospodarate that has exposed itself to the most blatant baseness.

Russia is thus shelling what deserves no protection and calling out to the Wallachians: You have proclaimed the sovereignty of the people and appealed to the protection of other powers, thus insulting the sovereignty of the Porte and my right to protect you.

The proclamation of popular sovereignty has in no way diminished the suzerainty of the Porte, for it has now been recognized by the general will of the people at a moment when they had made themselves independent. This has helped to control the intrigues that a certain class of society has always instigated to loosen the ties between Turkey and the Danubian principalities. The right of Porte has therefore been strengthened, not weakened. The situation is different, we must admit, with the protection of Russia.

Russia affirms in all its treaties its intention to maintain the integrity of Turkey. About the Danubian principalities, Russia bases all its treaties on the capitulations of these countries. But Russia itself undermines, through these same treaties, the integrity as well as the capitulations which it promises to maintain; for if it agrees with Turkey that the hosts of the principalities may, for once and for all, [Page 16] wise directly appointed, and must always be confirmed by both powers, not just by the Porte, after the election has taken place; furthermore, if it is stipulated in the regulations that the grievances of both countries against their princes are to be brought not only before the Eastern Porte, but also before the Russian Cabinet, then Russia, with this share of the above-mentioned two suzerainty rights, is thereby taking for itself a part of the suzerainty of the principalities which are integral parts of Turkey, and is de facto acting against the integrity which it formally denies. Taking for itself a part of the suzerainty is also acting contrary to the capitulations, because these do not grant Turkey the right to permanently transfer its suzerainty to other powers. It is further acting contrary to those capitulations whenever it interferes in the internal affairs of the principalities, as for example in the current constitutional question of Wallachia.

Ah! Russia will say, here is further proof that the plan of a Daco-Roman empire really exists, for if one returns to the legal status of the capitulations, then Austria must give up Bukovina and we Bessarabia. Our demands do not go that far; for we recognize not only right but also necessity; consequently, it is only a matter of not allowing any of the powers to interfere in the control of the others; and Russia does this through the share it takes in the suzerainty over the Principalities and through the way it understands its protection. In fact, consider well that in form the Principalities are integral parts of Turkey, but de facto they are ruled by Russia.

Russia should protect the principalities against any encroachment on their rights; it should assist them with sincere, well-intentioned, and unimportant advice; however, it must not undermine the integrity of the Ottoman Empire, nor gradually assimilate and incorporate Moldavia and Wallachia into its states through criminal and treasonous hosts who are disloyal to their sovereign.

Let us consider the question from a social point of view. Russia will present democratic socialist propaganda to the Wallachians! We maintain that these tendencies are already partly evident [Page 17] in the statutes that Russia had given to the Wallachians, but were partly promoted by the hospodars, whom Russia protected. Strange as this may sound, there is nevertheless nothing plausible about it, and to convince the reader, we need only introduce him to the conditions of the Danubian principalities.

After the Peace of Adrianople, we received new organic statutes from Russia, under the name Organic Regulations, and all previous state institutions that we had were abolished. Those institutions were purely aristocratic, in that power and prestige were concentrated only in the narrow circle of a few families The aristocracy willingly renounced its rights and adopted the Réglement organicique, which, instead of the aristocratic Senate, or Divan, as it was called, counterbalanced the power of the hospodars in a general assembly elected by boyars without distinction of rank. The power to legislate was now transferred from the few to the many and was thus the first step along a democratic path. But this step did not stop there; for the inevitable and foreseeable consequence of these same statutes was an innumerable increase in the number of voters and eligible voters, by which the princes believed they could stifle any opposition. A supply of boyars was always required to cover the extortion they committed, and thus the number of voters and eligible voters gradually increased tenfold, if not more, whereby legislation thus passed into the hands of very few boyars. This was not only a second step in a democratic direction, but also in a socialist one; for most voters and those eligible to vote had neither education, nor merit, nor wealth, nor were they peasants living off the earth by the sweat of their brow, but a new kind of proletarian in the pay of the princes. It was quite natural that from such an electoral body, both deserving and deserving deputies, not counting a few exceptions, would emerge. But if a country sees itself represented by people who are deserving, moral, what security does property have then? Who was the communist here, the government that always sought salvation in corruption, that offered justice for sale, and to achieve its goals only used those people who had nothing to lose, or [Page 18] those who proclaimed universal suffrage and granted landed property to the peasant in order to interest him in the land and to introduce an uncorrupted element into the electorate? We believe the answer is obvious.

After considering the question from a legal point of view, we will attempt to consider it from its political side as well. Our hearts tell us that where the law is to be found, it would be superfluous to ask whether politics approve of it; but unfortunately, experience, or rather custom, speaks against it.

We will not investigate whether the Orient, as the dispatch from the Russian Cabinet claims, should remain a matter to be negotiated between Russia and Turkey alone, excluded from international law. For we sincerely admit that we do not fully understand this assertion, and Austria, Germany, England, and France will probably best appreciate the passage referring to it, as their honor and interests demand. We do not believe, like the Cabinet on the Neva, that the Western states are powerless due to internal unrest; we are firmly convinced that they owe their independence only to themselves, not to foreign magnanimity. Accordingly, we will limit ourselves to investigating how, given the current situation in the Danubian Principalities, Russia could find its real, not apparent, benefit in settling them. The first question, therefore, is: What does Russia want in the Danubian Principalities?

To answer this question, we will cite to the reader two fragments from one of our letters, which was included in the appendix to the Allgemeine Zeitung of January 16, 1846, since we believe this is the shortest way to place the reader in the midst of our current circumstances. However much one may praise the Petersburg diplomacy, it nevertheless seems to have taken a false path here. When the Russian armies withdrew from Moldavia and Wallachia after the end of the last Turkish War, they left behind many sympathies that the kindness, insight, nobility, and merits of General Kisseleff had bestowed upon them. Now these [Page 19] sympathies have died out; Russia’s influence is limited solely to the ruling princes, whom it keeps in check with the fear of their disregard, and through whom it sees through everything that seems conducive to its aims. That this procedure is practically unsafe is beyond doubt; but since it forces one to turn a blind eye to all kinds of abuses committed by the princes and to ignore well-founded complaints against them, the nation’s trust is ultimately lost and yet maintaining that trust must be of great importance to Russia. The northern great power now seems to realize that it can no longer rely on the loyalty of the Moldavians and Wallachians, that the friendly feelings have turned into opposing ones, and that the hopes of the principalities are no longer directed towards the distant Neva, but rather towards the source of the most fertile and blessed river, the Danube, by lingering the longest over a mighty imperial city.

Russia now wants to make amends for this political error in Moldavia and Wallachia. Two paths are open to it for this purpose. It can still use the hospodars as instruments, expel everything that thinks and feels in the country, as has already happened in part, and perhaps even send it to Siberia to cleanse the lower Danube of all liberal elements and prepare it for incorporation with Russia. It can also seek to regain the sympathies of the country it has lost, regenerate the principalities through new, self-created justices, and unite them in accordance with Article 425 of their statutes. And since it will have restored their injured honor through the invasion of its army, it can also show the Moldavian Wallachians that Russia can be magnanimous and just.

Which of these two means will Russia prefer? That depends on the policy it intends to pursue in the Orient, and we believe that the great powers of Europe today find themselves in the position vis-à-vis the Orient and Russia that follows from the [Page 20] following fragment of our already quoted letter to the Allgemeine Zeitung is clear.

It seems to me to be erroneous to attribute the successes of Russian diplomacy in the Orient to a special skill peculiar to it, for the other powers have at least equally distinguished men; but the policy of the latter is striving to keep the present situation in Turkey unchanged. They view the moment when the rotten Ottoman Empire will finally collapse with a gloomy foreboding; they are not yet agreed within themselves about what they will see in its place, and therefore they are striving to hold on to the present. Not so Russia. This great power wants to destroy everything existing in the Orient, for since it is entirely clear about what it has to build anew there, it moves fearlessly towards the future, and in its work it is supported by the force of nature, whose law it is to undermine that which is weak with age until it is destroyed The other powers are fighting against nature; what wonder if they are defeated! Would it not be wiser to recognize Turkey’s situation as untenable, to abandon the status quo, and, before being forced to do so by unforeseeable events, to give it a rejuvenating political form? In this way, I believe, one would be more secure against possible contingencies; one would organize the Orient as one wants it, not shape it disorderly as the faits accomplish, and one could follow the course of nature, no longer striving in vain to drive it out of its order; for the present must give way to the future, being displaced by events that no earthly power can undo, just as no power can hinder the earth’s movement around its axis in order to hold onto what is due to the Orient today, prevent tomorrow!

But it will be replied, the Eastern question must not yet be solved, it is not yet ripe, one must only [Page 21] observe, not intervene; for the interests of the great powers are too different and opposed to lead to a war that would set back industry and the entire prosperity of Europe for many years. Precisely because the interests of the great powers are so different and opposed, because they could cause a war, one should work in time to reconcile them and agree on what needs to be done; for now, one still has the leisure to argue back and forth with one’s pen until one reaches a desired result by peaceful means. But if one is finally compelled to act by events that one cannot foresee, prevent, or master, then one does so without being composed; there is no time for reflection and negotiation. Under these auspices, war then becomes much more likely and much more dangerous.

These are the auspices under whose impression we find ourselves today. Events have taken place that have shattered the status quo, the prison of divine ideas, and now it is a matter of accomplishing all at once the tasks that were previously not gradually resolved, and which were always postponed. Russia has not wasted its time in the Orient; it has sought out the most important individuals there, learning their merits, inclinations, characters, and weaknesses, to have its tools ready at a given moment and to be able to distinguish its supporters from its opponents. Will it now spring to live and introduce a new order in the Orient by force of arms, or will it seek to win the sympathy of the nations? It can, with a dignified attitude, strive to maintain peace with the other powers, which certainly cannot idly watch Russia’s advance, and thereby arouse sincere sympathy among all nations, even more so since it would selflessly sacrifice certain advantages it enjoys in the Orient for the common good. The future will exclude us. But we hope that Russia knows well that only the very least can bring it lasting advantage, and that we sincerely mean it may be clear from the following. How has Russia gained prestige, how has it risen to the status of a great European power? Primarily through the Congress of Vienna, where, in agreement with the powers of [Page 22] Europa acted after fighting arm in arm with the European peoples against Napoleon. How did it lose diplomatic ground in Europe? Through the Eastern Question, which aroused general mistrust among both the rulers and the governed in Western and Central Europe. It should now approach this issue courageously, sincerely, with goodwill, in accordance with the spirit of the times (since it cannot fight against the tide), and with a consciousness of its dignity; it should allow the Danubian principalities to purge themselves of corruption, allow the regeneration of the principalities to take place through new, free institutions, and furthermore, it should no longer fire on the hosts against the just accusations of the people. And truly, Russia will safely make moral conquests on this path that it need not expect from its cannons, and only then will it be able to cry out with full consciousness: God is with us, for where the teachings of Christ are not, there God cannot be.

We conclude, after having considered the question, like the dispatch, from the standpoint of law, honor, and politics, with the remark that we do not wish to enter the investigation of what should be done in the interests of France, England, Germany, and Austria. It would be presumptuous of a Moldovan to try to draw these powers’ attention to what is clear. We have therefore limited ourselves merely to presenting the rights of the Principalities in their true light; it is the responsibility of those who direct the world’s affairs to enforce those rights in the interests of their peoples. Many will miss in this text a tone that is fashionable today, one that proudly thunders its fury from a pseudo-freedom against everything that rules on earth. We, on the other hand, belong to those who have not lost faith in peace and freedom, indeed even cherish the conviction that freedom can only go hand in hand with peace. We therefore consider it our duty not to further provoke the already agitated parties, and by not deviating an inch from what is right, we sought to avoid any agitation as much as possible, knowing full well that the abolition of freedom and law has caused great harm and, unfortunately, will continue to do so for a long time to come. With the firm confidence that the great powers will reach an understanding so as not to plunge nations into ruin, we cry out: God be with us, and with Him who defends the law. [Page 23]

Appendix.

The Russian circular note denies the Romanic Danubian principalities any sovereignty and claims that they are merely simple, tributary provinces of Turkey, mere integral parts of the Ottoman state. History, treaty law, and the current state of affairs in the powerful triumvirate nevertheless rise up against this well-calculated and well-aimed assertion, which is intended to deprive the political transformation process begun and further promoted by the principalities of even the semblance of law and the sweetness of legality in the eyes of Europe, and thus nip in the bud any sympathy from Western Europe.

History teaches that with the immigration of the Romanic tribe from the present Banat and southern Hungary into the two Danubian countries in the course of the 13th and early 14th centuries, two sovereign states arose there, ruled by their own self-elected voivodes, extending from the southern slopes of the Transylvanian Carpathians to the Black Sea, from the Dniester and Prut to the Danube, often waging successful wars with Hungary and Poland, repeatedly allied themselves with these then more powerful kingdoms as protective powers, granted them all the rights of supremacy and protection, but never and under no conditions gave up their independence, and least of all their sovereign internal governmental power, and of external sovereign rights only as much as was absolutely necessary to recognize the supremacy of the protective state. Which is why, despite this relationship, they still, in accordance with international law, by virtue of their remaining sovereignty, concluded alliances and alliances of oaths with neighboring powers through their own envoys, received envoys, and were thus recognized and treated by all powers as sovereign states of the second rank. In general, the position of the two Danubian principalities towards the crowns of Hungary and Poland in the Middle Ages was almost analogous to that of the German electoral states towards the Holy Roman Imperial crown, indeed much freer than that of the former, since they were essentially outside any close state alliance with Hungary or Poland, did not form an integral part of either state, and were considered to be independent states, bound to the foreign crown merely by the recognition of foreign suzerainty. Just as little, for example, was the electorate, later kingdom [Page 24] Prussia in the 18th century, despite its status as a constituent part of the adjacent Roman Empire, could be denied sovereignty, just as much as the two Romanesque principalities could be denied in the Middle Ages. When the two Romanesque principalities, namely Wallachia, first recognized the supremacy of Sultan Bayazid by treaty in 1393 under the voivode Mircea, but then under the voivode Vlad V, and then in 1460, granted supremacy to Sultan Mahmut II, the regent of Constantinople, Moldavia, however, came under Turkish suzerainty in 1515 under the voivode Bogdan, who recognized Sultan Selim as supreme lord, and later in 1583. This happened, incidentally, through voluntary submission and not by way of conquest. They expressly reserved all internal sovereignty of free self-government and the election of princes, apart from the Sultan’s right to confirm the elected prince and the right to an annual tribute granted to him. Of the external sovereign rights, however, they reserved as much as seemed at that time compatible with these very sovereign rights of the Porte. Accordingly, in the relevant treaties of submission of the principalities with the Porte in 1393, 1460, 1515, and 1583, the principalities were expressly granted the right of self-government according to their own ideas, for example the complete internal right of administration and execution, which includes in particular the right of life and death of the princes against their subjects, the right to wage war against their neighbors and to make peace with them at their own discretion, the resulting automatic right to be represented abroad by ambassadors, the right to elect their own voivode, who, however, requires the confirmation of the Sultan, and these two states always made full use of all these rights, as they later also waged war on their own soil by virtue of these capitulations, made peace, governed themselves unmolested, elected their own princes, received foreign ambassadors, and sent their own, without the Porte ever having made any interference in this regard. Now, in the narrower sense of international law, that state is called sovereign, which is independent of the will of other states, and therefore, whatever its internal constitution may be, is entitled to exercise its sovereign rights for itself and without external influence. Sovereignty is not revoked by any relationship the state may have with other states regarding vassals, feudal obligations, interest systems, subsidies, nor by the regent’s service to another sovereign state. The famous constitutional scholars Battel and Martens are therefore of the opinion that the two principalities are still legally to be regarded as completely sovereign. Martens says, particularly about the Wallachians: [Page 25] If one takes history seriously and adheres precisely to the wording, it is clear that it was not until 1460, that the Porte received the provostship and supremacy; that Wallachia was not incorporated; that the state has never lost the essential characteristic of sovereignty; that the state, as far as its constitution and civil government are concerned, is not to receive any assistance from anyone; that its sovereignty cannot be impaired by the loss of some rights belonging to state law, and that it is not obliged to recognize a foreign sovereign power over itself; Wallachia agreed to the payment of tribute and the recognition of supremacy only in order never to cease to be a sovereign state. Wallachia is a sovereign state, and neither a treaty, a tribute, an unequal alliance, nor supremacy itself (if there is even such a thing as international law in Europe) can deprive it of its sovereignty, since it possesses the right to govern itself, to legislate, to conclude treaties, to wage war, to make peace, and even the right of representation abroad. This is the judgment of one of the leading constitutional scholars of our time. And if Klüber vacillates between the attribution of sovereignty or semi-sovereignty to these two countries, and believes that their legal relationships under international law have not yet been fully established, his indecision stems solely from his complete ignorance of the above-mentioned fundamental treaties or so-called capitulations, by which the relationship between these countries and the Porte was legally established for all subsequent times, while Klüber only attempts to derive the legal relationship of the principalities to the Porte from the much later treaties of Russia by Kuchuk-Kainarji (1774), Iasi (1792), and Bucharest (1812), which even in this case are incomprehensible without knowledge of those old capitulations. Whether one counts the principalities as sovereign with Battel and Martens, or as semi-sovereign with Klüber, because of the sovereign right of confirmation of the elected court prince transferred to the Porte, one thing is certain: in both cases the right of internally independent self-legislation and self-government, as recognized by the Porte in treaties, cannot be objected to. This is all truer since the old peace treaties and other conventions expressly establishing this right, the capitulations of 1393, 1460, 1515 and 1583, from Russia to the Porte, were sometimes accepted, confirmed and guaranteed in their entirety through individual fireman and permitted interventions in the internal administration of these countries, and that some of the powers granted to these countries in the original treaties of subjection, for example the right of war, were exercised more by the native princes; thus in the former case, the conclusion of peace, and external representation, for a long time [Page 26] should be remembered that the Porte could not unilaterally acquire or assert any right contrary to the letter and spirit of the old treaties, since it is well known that limitation, a product of positive private law, does not exist between independent states without a contractual provision, and thus the Porte could not acquire any new right against the two principalities through expiration, which is a type of limitation, because it can nowhere be proven that the testaments had committed themselves to recognizing the Porte’s right of enforcement. In this respect, however, the same reason must be invoked, partly as the inadmissibility of a limitation, and partly as the fact that even the most prolonged toleration of foreign injustice in international relations, which appears expedient and prudent in the face of superior power, never deprives the right to exercise all one’s powers to the fullest extent at the appropriate time by remedying the injustice. In general, the current relationship of the principalities seems to be comparable to that of Egypt and Mehmed Ali to the Porte, insofar as the latter was established in 1840 and guaranteed by the four Great Powers. Here, too, a suzerainty right of the Porte and a free internal administrative and legislative right of the old pasha steps have been established. Here, too, the semi-sovereignty of the country and its ruler has been formally recognized by the European Great Powers, both through formal accreditation of diplomatic agents and general convoys, as well as through diplomatic negotiations with the ruler, the result of which sometimes appears to be treaties of the legislature with the European states. Here, too, Pasha’s right to wage war and conclude peace at his own discretion, if the sovereign rights of the Porte are not thereby impaired, is unchallenged. And just as Russia or the Porte are not entitled to dictate laws to the Egyptian governor or to interject against the introduction of a new constitution of his choosing, neither power is entitled to do so with regard to the principalities; for since the Porte itself, despite its suzerainty, cannot claim such a right of intervention, it was consequently not in a position to transfer this right to the protecting power. Overall, Russia is this time protecting its own right of protection, or guardianship, over the principalities rather than the violated right of the principalities themselves; indeed, the Protector is forcing the Suzerain to not recognize, and thus to violate, an indisputable right of the foes. And by all appearances, the Porte, precisely because of this anomaly, will assume the role of protector against the so-called Protector, who now acts as publisher, for example must return to the normal position assigned to the Porte by the old treaties with the princedoms, if it does not want to lose the sympathy of its countries and see its own existence endangered. So much from the standpoint of strict treaty and international law regarding the actual legal question.